Free Shipping On Orders $100+

Stay toasty on hardwater this winter with layers and insulation.

Leeson’s bold statement comes from an issue that was dedicated to celebrating our own anniversary, and the significant changes in our sport that occurred along the way. It was our way of saying, “We’ve come a long way, baby.”

Interestingly, the story “50 Most Influential Fly Fishers” ignited a firestorm of controversy. Countless emails, and letters, and Internet posts argued that we’d left someone important off the list, or that someone on the list shouldn’t be there. Everyone had a different opinion.

However, not one person argued with Ted Leeson’s thesis that breathable waders were the most important equipment advancement in our lifetimes. Fire helped primitive humans survive brutal weather, expand their range on different continents, and become the apex predator on this planet. In our time, breathable waders have made us more comfortable, happier, able to spend more hours, days, and seasons on the water. They helped us catch more fish with a whole lot less discomfort for more of the year.

Simms manufactured that first pair of breathable waders in 1993 using a breathable membrane from W.L. Gore, and within five years, neoprene waders were just a relic of the past. Today, Simms, Patagonia, Orvis, Grudéns, Skwala, Redington, Chota, and many other companies sell breathable waders using either the Gore-Tex brand or an alternative breathable membrane. The successful introduction of a wader that keeps water out, but actively passes water vapor to the outside—even while underwater—has truly revolutionized our sport.

If you’ve taken up fly fishing within the last 20 years, you likely only know a world of breathable waders. You don’t remember the “before times” of rubber bootfoot waders. They were heavy, likely to drown you if you took a spill, and uncomfortable to walk in. The rubber didn’t react kindly to ultraviolet radiation and cracked in the sun. You could use patches from a bicycle tire repair kit to cover the cracked areas, but you were constantly fighting a losing battle.

Neoprene waders replaced rubber waders, and dominated the fly-fishing market in the late 1980s and early 1990s. They had some advantages over rubber waders in that they added some buoyancy, and since they were also stretchy, they didn’t have to be as cavernous. In fact, they were quite form fitting, which was not flattering for the body types of many fishermen. You might say they were a precursor to the yoga pants of today, except they were made from 3.5 or 5mm neoprene with glued and taped waterproof seams. To continue the yoga analogy, neoprene waders were the equivalent of “hot yoga” or your own portable Native American sweat lodge. In a day of walking and fishing, the neoprene would catch all the moisture coming from your body, and turn the inside of the waders into a soupy mess.

It didn’t matter if neoprene waders leaked or not: At the end of the day your clothes were wet. Even people who believed they didn’t sweat much ended up soggy, because in normal conditions, you don’t notice the warm moist air coming from your skin. But when it’s trapped in a cocoon of neoprene, it turns to liquid. At the end of the day you could turn neoprene waders inside out and dry them, but after a summer of sweating cycles, the inside of those waders would start to stink like a set of gym clothes you used for 60 days without washing. It was horrendous. There had to be a better way.

K.C. Walsh fell in love with fly fishing and with Montana when he was 12 years old. His grandparents rented a house on the Bitterroot River, and Walsh joined them for part of the summer. “My grandfather was an avid fly fisherman and got me into it at a young age,” said Walsh. “I just had a terrific time with them up here. In the back of my mind I always had this vision of living in Montana.”

When he finished graduate studies at The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, he shuttled a car to the West Coast for a friend just so he could visit Bozeman along the way. He ended up getting a job in Los Angeles, and lived in what he describes as a “semi-dangerous area” and spent six years just working and saving money, waiting for the right opportunity to make a move to Montana.

In 1992 he started looking at buying Simms, a company that was founded by John Simms but at that time was owned by Life Link International.

“When I was doing my due diligence I found out they had a very sophisticated engineering crew for a company of that size,” said Walsh. “I became super interested in the company because they had an exceptional innovation staff. They introduced breathable waders at the IFTD show in Sept. 1992, and that emerging relationship with W.L. Gore really drew me to the business. I knew this was going to be a big opportunity for us. I was super interested in the wader business, but the apparel offering at Simms was also pretty awful, and there was also huge potential in wading boots. There was just a lot to work with there.”

At that time, Simms had 15 employees and a 9,000-square-foot facility.

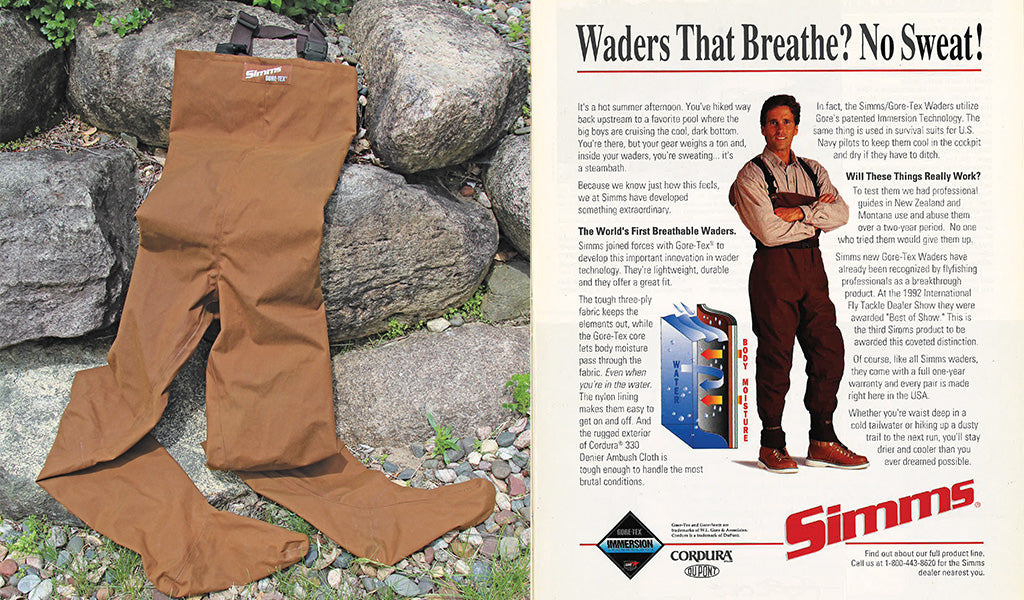

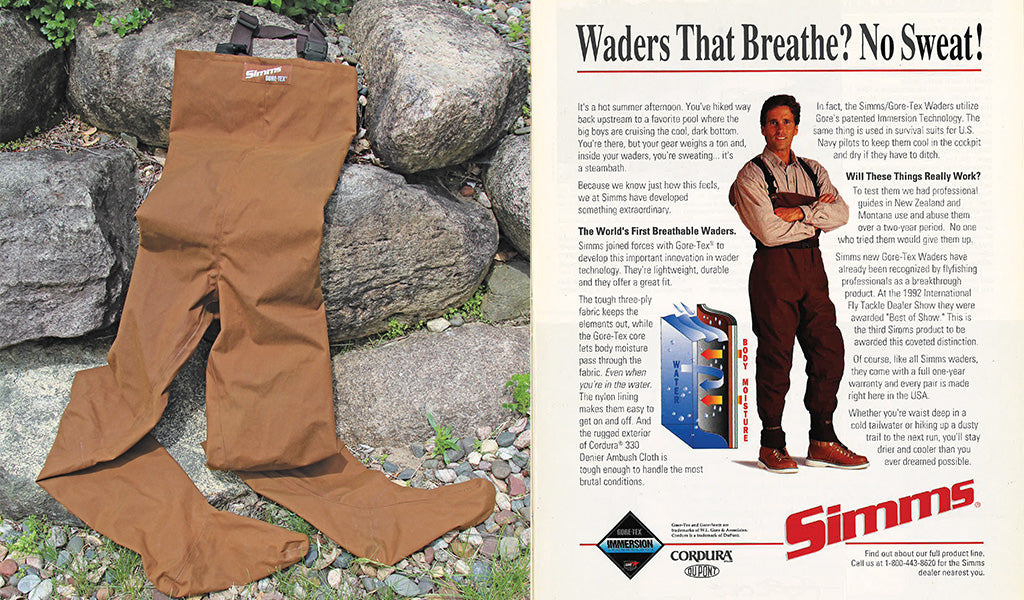

K.C. Walsh acquired the company on May 1, 1993, and the first breathable waders in the world were on sale about a month later. The full-page ad that appeared in the July 1993 issue of Fly Fisherman boomed “Waders that Breathe?” and indeed, consumers had many questions.

When the first pair of breathable waders hit retail shelves, the new technology was not instantly adopted, or even understood. The neoprene waders of the day looked and felt indestructible and insulated you against cold water. The new flimsy, goofy-looking “fabric waders” from Simms didn’t look like they would hold up for one fishing trip, let alone a season. And they were far more expensive than neoprene waders. Premium 3.5 mm neoprene waders cost $129, and the new breathable waders from Simms cost $249.95. Given what we know about inflation over the past 30 years, that was a lot of money.

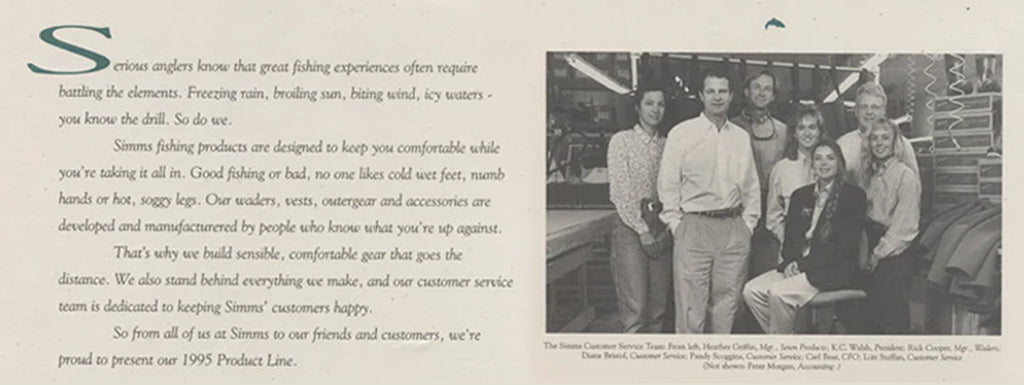

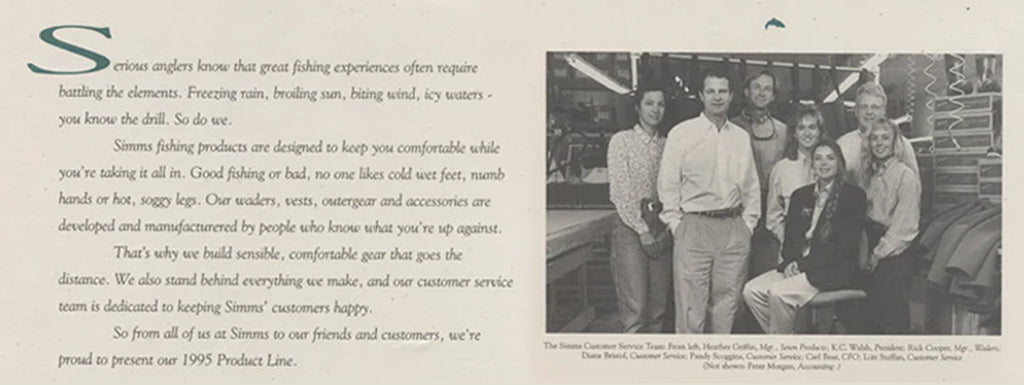

According to Diane Bristol, who is today the longest-tenured employee at Simms, and vice president of community and culture, “At every consumer show we could always count on at least one person coming through the booth and declaring that the waders cost more than their house payment.”

Consumers were resistant to change, but two important factors made breathable waders a success: public education and product improvement and innovation.

The first breathable waders used a Gore-Tex breathable membrane that introduced a new Immersion Technology, which was different than the Gore-Tex membrane that was already in wide use in outdoor outerwear, where it worked to shield you from precipitation. But in the first pair of waders, the original Cordura 504 face fabric allowed almost every thorn or bramble to pierce through the outer layer, creating pinhole leaks in the Gore-Tex membrane.

Gore only allowed Simms to sell 1,500 pairs of waders in the first year, and since Simms was not an “approved” Gore-Tex manufacturer, the waders were actually manufactured by a third party.

According to K.C. Walsh, “Somewhere between 30 to 40 percent of those 1,500 waders came back with leaks, and when we started seeing those gigantic return rates it became a code red problem. Fixing that problem was really my first order of business.”

Walsh says Simms used an Instron tester with acupuncture needles to simulate fine nettles and thistles, and then tested fabrics from all over the world.

The solution was a brand new textile Simms found in Japan called “exploded microfiber.” In this product, a single fiber has 29 or more layers held together with a polymer. They weave these fibers together and when they finish the fabric, they melt the polymer and all 29 of those fibers explode and it becomes a super-dense material.

According to Walsh, the exploded microfiber broke the needles on the testing machine without puncturing. That new material went into the first pair of Guide Waders released in 1995.

The fabric stockingfeet of the first iteration were also problematic because they were badly misshapen. “The damn things would slip down into the toes of your boot,” said Walsh. “It was incredibly annoying. People were putting rubber bands around their ankles just to hold their waders up.”

“The solution of course was the neoprene stockingfoot,” said John Frazier, manager of PR, Content + Digital Marketing at Simms. “We knew it was the right idea and the right material, but attaching the 3mm neoprene stockingfoot to the thin Gore-Tex fabric was very difficult. It was a challenge to get a durable, secure seal.”

The company had to experiment with many different manufacturing processes and adhesives before they figured out how to make that joint actually work. To this day, when you tour the Simms factory, visitors can see every part of the manufacturing process, except the area where the neoprene stockingfeet are attached to the rest of the waders. That is the Area 51 of the Simms factory, and outsiders are not allowed to see it.

It also took a while for Simms to perfect the fabric package. Early on, tightly woven microfibers for the face fabric made the waders much tougher, but it was still a 3-layer fabric with a tricot liner on the inside. Simms experimented with sewing two pieces of this 3-layer fabric together for the leg portion, which did in fact increase durability, but it compromised comfort and mobility. Simms eventually worked with Gore-Tex to make a 5-layer fabric, which was the standard for many years. Today, Simms uses a 4-layer fabric package in its top-end waders, and 4 layers is pretty much the standard across the wader industry.

Like the stockingfeet, it also took a few years for Simms to figure out exactly where to put the seams on the waders. When their first breathable waders came to market, the seams were similar to pants seams—on the inside of the legs, and the joints there were bulky because there was no way to build in articulation, which caused abrasion leaks at the knees. It was a consistent problem identified by the Simms repair center, and it was another reason why the first attempts at breathable waders had a reputation for being leaky. Once they moved the seams to the front and the back of the legs, Simms was able to improve the articulation in the legs and dramatically increase the longevity of the waders.

Fine tuning the seams and also perfecting the fit of the waders for body shapes of all sizes were keys to creating waders that performed better and more comfortably than anything on the market.

Beyond perfecting the product, there was a ton of public education that needed to happen as well. In 1993, most people didn’t know how “breathable” fabrics worked, and most people didn’t believe or understand how water could pass from inside the wader to the outside while standing in water. So Simms was aggressive with consumer trade shows, showing people one at a time how it worked. They would dip their hand in water, put the hand inside a dry Gore-Tex glove, immerse the hand in cold water, and wiggle their fingers—basically wading in a river. When they took their hand out of the water and removed the glove, voila! Their hand was dry again. It was like a magic trick that proved show after show and year after year that you don’t have to be wet inside your waders. The micro-porous membrane blocks water molecules from entering, but allows (smaller) water vapor to pass, and the warmth of your body creates that vapor and even forces it out of the waders due to the colder temperature on the outside.

Within a few years of perfecting the design and educating the public, breathable waders became the standard across the globe, and neoprene waders basically disappeared from the fly-fishing marketplace.

As a side note, K.C. Walsh sold Simms in 2022 for $192.5 million, and the company had $100+ million in revenue that year. Today, the company has a 90,000-square-foot manufacturing space and nearly 200 employees in Montana alone.

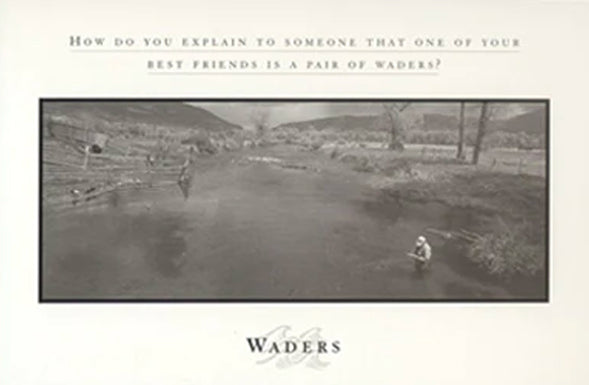

Every wader company in the fly-fishing space now uses breathable fabrics, their own secret sauce of seam design, and other features like waterproof pouches, handwarmer pockets, zingers, fly box pockets, and other conveniences to make their own unique breathable waders, but there is a lineage and a history for all fly fishers that goes back 30 years, to a moment when one brand decided to make a truly innovative product that would change where, when, and how we fly fish.

Leeson’s bold statement comes from an issue that was dedicated to celebrating our own anniversary, and the significant changes in our sport that occurred along the way. It was our way of saying, “We’ve come a long way, baby.”

Interestingly, the story “50 Most Influential Fly Fishers” ignited a firestorm of controversy. Countless emails, and letters, and Internet posts argued that we’d left someone important off the list, or that someone on the list shouldn’t be there. Everyone had a different opinion.

However, not one person argued with Ted Leeson’s thesis that breathable waders were the most important equipment advancement in our lifetimes. Fire helped primitive humans survive brutal weather, expand their range on different continents, and become the apex predator on this planet. In our time, breathable waders have made us more comfortable, happier, able to spend more hours, days, and seasons on the water. They helped us catch more fish with a whole lot less discomfort for more of the year.

Simms manufactured that first pair of breathable waders in 1993 using a breathable membrane from W.L. Gore, and within five years, neoprene waders were just a relic of the past. Today, Simms, Patagonia, Orvis, Grudéns, Skwala, Redington, Chota, and many other companies sell breathable waders using either the Gore-Tex brand or an alternative breathable membrane. The successful introduction of a wader that keeps water out, but actively passes water vapor to the outside—even while underwater—has truly revolutionized our sport.

If you’ve taken up fly fishing within the last 20 years, you likely only know a world of breathable waders. You don’t remember the “before times” of rubber bootfoot waders. They were heavy, likely to drown you if you took a spill, and uncomfortable to walk in. The rubber didn’t react kindly to ultraviolet radiation and cracked in the sun. You could use patches from a bicycle tire repair kit to cover the cracked areas, but you were constantly fighting a losing battle.

Neoprene waders replaced rubber waders, and dominated the fly-fishing market in the late 1980s and early 1990s. They had some advantages over rubber waders in that they added some buoyancy, and since they were also stretchy, they didn’t have to be as cavernous. In fact, they were quite form fitting, which was not flattering for the body types of many fishermen. You might say they were a precursor to the yoga pants of today, except they were made from 3.5 or 5mm neoprene with glued and taped waterproof seams. To continue the yoga analogy, neoprene waders were the equivalent of “hot yoga” or your own portable Native American sweat lodge. In a day of walking and fishing, the neoprene would catch all the moisture coming from your body, and turn the inside of the waders into a soupy mess.

It didn’t matter if neoprene waders leaked or not: At the end of the day your clothes were wet. Even people who believed they didn’t sweat much ended up soggy, because in normal conditions, you don’t notice the warm moist air coming from your skin. But when it’s trapped in a cocoon of neoprene, it turns to liquid. At the end of the day you could turn neoprene waders inside out and dry them, but after a summer of sweating cycles, the inside of those waders would start to stink like a set of gym clothes you used for 60 days without washing. It was horrendous. There had to be a better way.

K.C. Walsh fell in love with fly fishing and with Montana when he was 12 years old. His grandparents rented a house on the Bitterroot River, and Walsh joined them for part of the summer. “My grandfather was an avid fly fisherman and got me into it at a young age,” said Walsh. “I just had a terrific time with them up here. In the back of my mind I always had this vision of living in Montana.”

When he finished graduate studies at The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, he shuttled a car to the West Coast for a friend just so he could visit Bozeman along the way. He ended up getting a job in Los Angeles, and lived in what he describes as a “semi-dangerous area” and spent six years just working and saving money, waiting for the right opportunity to make a move to Montana.

In 1992 he started looking at buying Simms, a company that was founded by John Simms but at that time was owned by Life Link International.

“When I was doing my due diligence I found out they had a very sophisticated engineering crew for a company of that size,” said Walsh. “I became super interested in the company because they had an exceptional innovation staff. They introduced breathable waders at the IFTD show in Sept. 1992, and that emerging relationship with W.L. Gore really drew me to the business. I knew this was going to be a big opportunity for us. I was super interested in the wader business, but the apparel offering at Simms was also pretty awful, and there was also huge potential in wading boots. There was just a lot to work with there.”

At that time, Simms had 15 employees and a 9,000-square-foot facility.

K.C. Walsh acquired the company on May 1, 1993, and the first breathable waders in the world were on sale about a month later. The full-page ad that appeared in the July 1993 issue of Fly Fisherman boomed “Waders that Breathe?” and indeed, consumers had many questions.

When the first pair of breathable waders hit retail shelves, the new technology was not instantly adopted, or even understood. The neoprene waders of the day looked and felt indestructible and insulated you against cold water. The new flimsy, goofy-looking “fabric waders” from Simms didn’t look like they would hold up for one fishing trip, let alone a season. And they were far more expensive than neoprene waders. Premium 3.5 mm neoprene waders cost $129, and the new breathable waders from Simms cost $249.95. Given what we know about inflation over the past 30 years, that was a lot of money.

According to Diane Bristol, who is today the longest-tenured employee at Simms, and vice president of community and culture, “At every consumer show we could always count on at least one person coming through the booth and declaring that the waders cost more than their house payment.”

Consumers were resistant to change, but two important factors made breathable waders a success: public education and product improvement and innovation.

The first breathable waders used a Gore-Tex breathable membrane that introduced a new Immersion Technology, which was different than the Gore-Tex membrane that was already in wide use in outdoor outerwear, where it worked to shield you from precipitation. But in the first pair of waders, the original Cordura 504 face fabric allowed almost every thorn or bramble to pierce through the outer layer, creating pinhole leaks in the Gore-Tex membrane.

Gore only allowed Simms to sell 1,500 pairs of waders in the first year, and since Simms was not an “approved” Gore-Tex manufacturer, the waders were actually manufactured by a third party.

According to K.C. Walsh, “Somewhere between 30 to 40 percent of those 1,500 waders came back with leaks, and when we started seeing those gigantic return rates it became a code red problem. Fixing that problem was really my first order of business.”

Walsh says Simms used an Instron tester with acupuncture needles to simulate fine nettles and thistles, and then tested fabrics from all over the world.

The solution was a brand new textile Simms found in Japan called “exploded microfiber.” In this product, a single fiber has 29 or more layers held together with a polymer. They weave these fibers together and when they finish the fabric, they melt the polymer and all 29 of those fibers explode and it becomes a super-dense material.

According to Walsh, the exploded microfiber broke the needles on the testing machine without puncturing. That new material went into the first pair of Guide Waders released in 1995.

The fabric stockingfeet of the first iteration were also problematic because they were badly misshapen. “The damn things would slip down into the toes of your boot,” said Walsh. “It was incredibly annoying. People were putting rubber bands around their ankles just to hold their waders up.”

“The solution of course was the neoprene stockingfoot,” said John Frazier, manager of PR, Content + Digital Marketing at Simms. “We knew it was the right idea and the right material, but attaching the 3mm neoprene stockingfoot to the thin Gore-Tex fabric was very difficult. It was a challenge to get a durable, secure seal.”

The company had to experiment with many different manufacturing processes and adhesives before they figured out how to make that joint actually work. To this day, when you tour the Simms factory, visitors can see every part of the manufacturing process, except the area where the neoprene stockingfeet are attached to the rest of the waders. That is the Area 51 of the Simms factory, and outsiders are not allowed to see it.

It also took a while for Simms to perfect the fabric package. Early on, tightly woven microfibers for the face fabric made the waders much tougher, but it was still a 3-layer fabric with a tricot liner on the inside. Simms experimented with sewing two pieces of this 3-layer fabric together for the leg portion, which did in fact increase durability, but it compromised comfort and mobility. Simms eventually worked with Gore-Tex to make a 5-layer fabric, which was the standard for many years. Today, Simms uses a 4-layer fabric package in its top-end waders, and 4 layers is pretty much the standard across the wader industry.

Like the stockingfeet, it also took a few years for Simms to figure out exactly where to put the seams on the waders. When their first breathable waders came to market, the seams were similar to pants seams—on the inside of the legs, and the joints there were bulky because there was no way to build in articulation, which caused abrasion leaks at the knees. It was a consistent problem identified by the Simms repair center, and it was another reason why the first attempts at breathable waders had a reputation for being leaky. Once they moved the seams to the front and the back of the legs, Simms was able to improve the articulation in the legs and dramatically increase the longevity of the waders.

Fine tuning the seams and also perfecting the fit of the waders for body shapes of all sizes were keys to creating waders that performed better and more comfortably than anything on the market.

Beyond perfecting the product, there was a ton of public education that needed to happen as well. In 1993, most people didn’t know how “breathable” fabrics worked, and most people didn’t believe or understand how water could pass from inside the wader to the outside while standing in water. So Simms was aggressive with consumer trade shows, showing people one at a time how it worked. They would dip their hand in water, put the hand inside a dry Gore-Tex glove, immerse the hand in cold water, and wiggle their fingers—basically wading in a river. When they took their hand out of the water and removed the glove, voila! Their hand was dry again. It was like a magic trick that proved show after show and year after year that you don’t have to be wet inside your waders. The micro-porous membrane blocks water molecules from entering, but allows (smaller) water vapor to pass, and the warmth of your body creates that vapor and even forces it out of the waders due to the colder temperature on the outside.

Within a few years of perfecting the design and educating the public, breathable waders became the standard across the globe, and neoprene waders basically disappeared from the fly-fishing marketplace.

As a side note, K.C. Walsh sold Simms in 2022 for $192.5 million, and the company had $100+ million in revenue that year. Today, the company has a 90,000-square-foot manufacturing space and nearly 200 employees in Montana alone.

Every wader company in the fly-fishing space now uses breathable fabrics, their own secret sauce of seam design, and other features like waterproof pouches, handwarmer pockets, zingers, fly box pockets, and other conveniences to make their own unique breathable waders, but there is a lineage and a history for all fly fishers that goes back 30 years, to a moment when one brand decided to make a truly innovative product that would change where, when, and how we fly fish.

The best waders in the world are made by anglers in Bozeman, Montana. From a blank roll of GORE-TEX fabric, the same hands that double-haul sink tips and stroke drift boat oars cut, sew, and tape every wader that bears their mark.

Fly Fisherman Magazine celebrates the 30th anniversary of what's arguably considered the most significant innovation in fly fishing — waterproof/breathable waders.

Cart

Your cart is empty

From waders to tackle, we have all the gear to make your fishing trips unforgettable.

Cart (0)